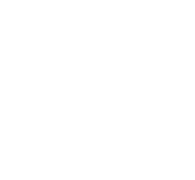

SHOW RUNNER Lisa Hennessy

By Ed Leibowitz, Illinois Alumni Magazine I January 12, 2022

On a crisp, clear afternoon in February 2021, Lisa Hennessy, ’91 LAS, returned to the U of I for the first time since her graduation. Tan and fit, her blond hair bleached by the sun, she looked for all the world like a pure product of Southern California, though she’s Illinois born and raised.

Stepping onto the Quad, Hennessy immediately came face to face with Alma Mater, who greeted her with open, bronze arms. “It was literally the first thing I saw,” she recalls. “This beautiful iconic statue welcoming me to my home.”

For her three-hour, self-guided tour, Hennessy navigated without Google Maps, preferring to find her favorite haunts by memory. “The Quad,” she says, “is a great north star.”

The old KAMS bar had been torn down, though a new one had arisen elsewhere in town. She had no problem finding Weston Hall, where she lived as a freshman, nor her sorority, Gamma Phi Beta, where she served as social chair. “I give a lot of credit to that job,” Hennessy says. “Ever since then, I’ve loved planning events.”

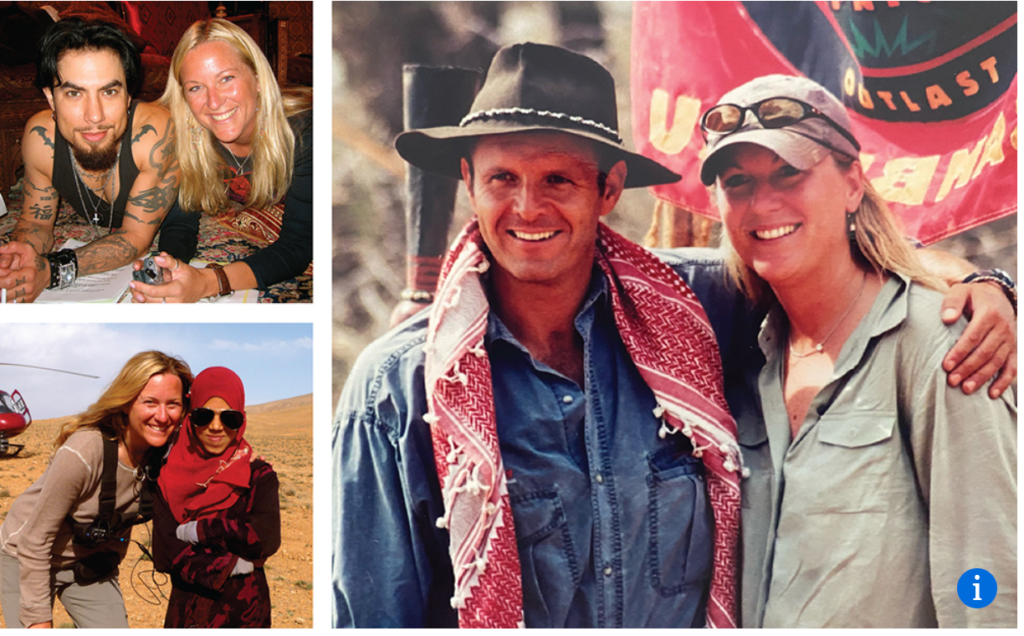

You may be among the many millions of television viewers who’ve seen some of Hennessy’s post-college “events.” She is one of the chief architects of reality television, executive producing the groundbreaking show Eco-Challenge and helping to develop Survivor in the 1990s. The following decade, she produced The Contender (in which young boxers competed under the watchful eye of Sylvester Stallone), and served as executive producer of Rock Star: INXS (in which contestants vied to become the next lead singer of the platinum-selling Australian band). During the 2010s, she went on to executive produce Expedition Impossible and The Biggest Loser.

Hennessy’s work has taken her from the South Island of New Zealand to the Patagonian mountains of South America to the jungles of Krabi, Thailand (where a posse of macaque monkeys tried unsuccessfully to steal her two-way radio).

Her walk across Campustown brought back wonderful memories, but like so many of her adventures, it took place during her regular course of work.

Since September 2020, Hennessy has been spending quality time on the nation’s campuses shooting episodes of The College Tour. Hosted by Alex Boylan, her business partner and co-executive producer, the program streams on Amazon Prime as well as on The College Tour app, and aims to tell a university’s story through the experiences and personal stories of its students.

High school juniors and seniors are the target audience, including those unable to visit faraway universities in person, either because they lack the travel funds, or, more widely over these past two years, because of travel restrictions and campus shutdowns in the midst of a pandemic.

“It’s the series you wish you had when you were looking at schools,” Hennessy says.

In the U of I episode, we meet Kennedy Campbell, a pre-med student who launched a physician-mentoring program, as well as Mike Skibski, a business major who co-developed an app, launched a club for the Rubik’s Cube-obsessed and released his first indie folk album.

Also in the mix is Mihir Vardhan, an engineering student from India who was enlisted by one of his professors to help develop an artificial, electromagnetically actuated animal spine.

The students also talk about their desires and expectations for the future.

One-way ticket to L.A.

As for Hennessy, life after graduation meant taking an entry-level position in the garbage industry. Her father’s best friend from boyhood headed the Chicago office of Waste Management Inc., one of the nation’s largest waste haulers. “My dad thought it was time for me to get a real job,” Hennessy recalls. “I didn’t have to apply.”

Although she would hardly be getting her hands dirty as an assistant sales coordinator, Hennessy, like all new hires at Waste Management, was required to spend a week riding shotgun in a garbage truck while it made its rounds. She had some interesting conversations with the drivers, while enduring the stench and constant clanking emanating from the rig’s rear.

Sometime during that week, Hennessy had a revelation, asking herself, “What am I doing? I’m not meant to be here.”

Hennessy’s childhood wasn’t particularly adventurous. She was raised in Park Ridge, a Northwestern Chicago suburb, in the same home with a front porch where her mother grew up. “We lived in a really lovely suburban bubble—an all-American upbringing,” Hennessy recalls.

During her time at Illinois, she longed to be part of the global community—to learn about the lives and experiences of people from other continents. After her sophomore year, she became a camp counselor in Maine—which seemed like a pretty exotic locale to her at the time—and where she made friends with staffers from England and Ireland. For her junior year, Hennessy enrolled in the U of I’s Institute of European Studies Abroad and went to Vienna. “That,” she recalls, “really took the blinders off.”

Bowing out of Waste Management, Hennessy left for Los Angeles with a one-way ticket and about $500 to her name. She crashed at a fellow alum’s place for awhile, then moved into an apartment with a roommate. She landed an internship at a PR company where she worked on an anti-smoking campaign during the day, while bartending and waitressing at an Italian restaurant during the evening.

It was six months after her arrival that her roommate came home with a brochure from a tiny production company that she’d begun interning for. Hennessy picked up the flyer and started reading about a project called Eco-Challenge Utah. Teams would race cross the state’s canyons, cliffs, deserts and lakes at a breakneck pace—canoeing, biking, rope climbing, horseback riding—to the finish line, where the winners would collect a $100,000 prize.

The production company was run by an entrepreneur named Mark Burnett, a former British Army parachute-squad commander who didn’t have a producing credit to his name. Hennessy met with Brian Terkelsen, who was then Burnett’s business partner. He hired her on the spot and told her they’d be flying to Utah together the next morning to do some prep work. But Hennessy told him she’d have to give her current employers two weeks’ notice, so Terkelsen hired someone else.

That next morning, Hennessy drove to LAX and made a beeline to Terkelsen’s departure gate before his 6 a.m. flight to Salt Lake City (such things were possible in the pre-9/11 years). She convinced the Delta rep at the gate counter to hand Terkelsen a postcard when he checked in. The postcard read: “I should be on this flight—not this postcard—but I know I was meant to work with you.”

After that bold gesture, Hennessy had little doubt she’d get the job. “If you knock down the door to get in,” she says, “then look them in the eye and have a smile on your face, it’s hard [for them] not to hire you.” Sure enough, Hennessy was brought on board with Burnett and Terkelsen—which raised the number of total staff to four.

Reality TV is born

The logistics of Eco-Challenge would have been difficult enough for an established studio—never mind capturing the exploits of multiple teams across hundreds of miles of rugged terrain on video without the benefits of cell phones or email. And Burnett’s four-person operation was hardly a seasoned one. “We were just this small production company,” Hennessy says, “and we had to pull things off on that kind of scale.”

Nor could they learn from the experiences of production companies that had made similar shows in the past, because there had never been a show remotely like Eco-Challenge. “We were creating the model,” Hennessy says. “And to do that, we had to be confident and take ownership.”

Hennessy would produce Eco-Challenge for the entirety of its nine-season run. Under her aegis, the field of play expanded across the globe—from Borneo to British Columbia to the entirety of the Kingdom of Morocco, ultimately earning her an Emmy Award nomination.

Eco-Challenge is widely regarded as the first modern reality show—in which competition is fierce, and winning it all involves physical and mental prowess, teamwork, resilience, a little cunning and a superhuman ability to keep one’s composure during situations that would drive most people to the brink of insanity.

That breakthrough show cast the mold for future reality shows that turned Burnett’s little shop into a $500 million company. His follow-up series, Survivor, is a perpetual juggernaut now entering its 21st season.

Hennessy’s more recent work has focused on ordinary people trying to emerge from extraordinarily difficult circumstances. On The Contender, many of the young boxing contestants were striving to bring their families out of poverty. As for the morbidly obese contestants on The Biggest Loser, Hennessy says, “the show clearly gave them a powerful toolkit they could use for the rest of their lives.”

There are also contestants who walk away from their season finales with a desire to break into Hollywood. “A lot of people who’ve competed on reality shows,” Hennessy says, “moved to L.A. because they want to pursue TV.”

Her current business partners, Burton Roberts and Alex Boylan, are prime examples.

Roberts was introduced to audiences in 2003 as a member of the Drake tribe in Survivor’s seventh season. Voted off the island, he was banished to the Outcast tribe, whom he convinced to vote him back onto the island by promising that he would never lie for the rest of the season. He kept his word, to his detriment, proving himself to be perhaps the most honest contestant in the program’s history.

For his part, Boylan won season two of The Amazing Race—sprinting to victory on a San Francisco bluff and joining his teammate and friend, Chris Luca, in a massive bear hug with show host, Phil Keoghan, after battling their way across five continents and 52,000 miles.

Boylan met Hennessy at a dinner with Roberts in 2011. “From that moment, Lisa and I became fast friends,” he says, “and we’ve been friends for many years.”

Hennessy joined forces with Boylan and Roberts in 2017 to produce DreamJobbing, in which contestants are given the opportunity of a lifetime to pursue their dream careers. In one episode, a college student intent on pursuing a photojournalism career lands a two-week assignment documenting the people, towns and mountains he encounters travelling across Norway. In another episode, a filmmaker who wants to break into the travelogue business is given 10 days to shoot the sights, natural splendor and people of Thailand—spanning Bangkok, Chiang Mai and Phuket.

Boylan came up with the concept for The College Tour while his niece was looking at schools. “She was able to take one [college-scouting] trip, when she came to visit me in L.A.,” he says. “Then with COVID-19, the journey to figure out where to go to school became a massive challenge for her. I’d never created a show out of a problem. But this was a very simple problem that we turned into episodic television.”

Boylan is at no loss for words to describe what Hennessy brings to their partnership. “Lisa is a powerhouse,” he says. “I don’t know whether there is a more experienced show runner or executive producer out there. And apart from Lisa’s organizational and management skills running big operations, she’s also extremely creative. She always has her finger on the pulse of what the audience is looking for and what’s really going to matter.”

Fighting social media addiction

In 2006, when Fear Factor marched its contestants into a dark pit and then dumped hundreds of rats on top of them, and when The Real Housewives of Orange County began debating the virtues of breast implants and Botox, reality TV was widely declared a cultural catastrophe.

While Hennessy has steered clear of the loudmouth and gross-out programming that often gave reality TV shows a bad name, she believes the negative impact of even the most egregious examples was exceedingly mild compared to today’s dominant cultural addiction.

“Compared to social media,” she says, “it’s not even close.”

In February 2017, Hennessy provided some powerful evidence for that argument when she and Boylan transported five Instagram- and Facebook-addicted millennials to Southeast Asia to film a documentary called Escape: A Digital Detox in Thailand.

Just before boarding the train that would take them into a 10-day adventure through pristine wilderness, a woman in traditional Thai dress confiscated all of their iPhones and Androids.

“Especially among the girls, there’s this false reality,” Hennessy says.

“They’re constantly comparing them-selves against these idealized versions of other girls on social media. And in our show, you could see that pressure being taken off. The young women didn’t have to pose for selfies. They could just be themselves.”

After 10 days of exploring and connecting, the millennials were reunited with their devices. Some were not too enthusiastic about the prospect of plunging back into a social media–saturated existence, where they would once again be obligated to manufacture glorified versions of themselves, and where everything they shared would be scrutinized and judged.

“When they got their cellphones back, they were so confused,” Hennessy recalls. “A couple of them didn’t want to leave where they were—because for the first time in a long time, they got to feel what it was like to be present.”